(Reformatted for Web Display)

A MANIFESTO

DIRECTED TO THE NEW AESTHETICS OF STEREO SPACE IN THE VISUAL

ARTS AND THE ART OF PAINTING

November 12, 1972

© Roger Ferragallo

Painting is reborn…….Enter the new awareness of Stereo Space and a New Aesthetics …….The centuries long conquest of plastic forms within a monoscopic pictorial space is ended……..A new era lies ahead for the visual arts…….The living third dimensional space-field awaits its birth. It asks nothing more than the trance-like stare of the middle eye to invoke Cyclops to waken from his 35,000 year sleep. This primeval giants reward will be the sudden revelation and witness to the dematerialization of the picture surface into an aesthetics of pure space where visible forms will materialize and release themselves—forms that are suspended, floating, hovering, poised, driving backward and forward, near enough to touch and far enough away to escape into the void………...So now enter a new aesthetic empathy, meditation, subjective intensity and an unparalleled form-space generation and communication.All of this exciting injunction could have been declared 134 years ago had it not been for the invention of photography. But at that time, 1838, the full investigation of form within the limits of the monoscopic surface had not yet been fully realized: the genius of Cezanne, Picasso, Braque, Duchamp, Balla, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Moholy-Nagy, Pollach and Escher lay ahead. Awaiting the future, too, would be the subjection of the picture plane to the forces of sculpture with such explosive consequences that our galleries and museums are graveyard and garden of plastic visual forms rented from the ribs of paintings. Looking back to 1838, one gazes with astonishment at the paper presented to the philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London on June 21, 1838 by Charles Wheatstone. Entitled “ON SOME REMARKABLE AND HITHERTO UNOBSERVED, PHENOMENA OF BINOCULAR OF BINOCULAR VISION”, this paper must now be recognized as describing one of the most remarkable techno-visual discoveries in the 35,000 years of the History of Art. This paper revealed a discovery as stunning as were the great polychrome visions painted by Magdalenian artists. Its contents were as innovative as was the first portrayal of overlapping planes and depth by the great neolithic cultures. It’s thesis was a powerful as the conquest of the third dimension rendered by Greek and Pompeian painters as focused in the Villa of Mysteries—yes, as revolutionary as was Brunelleshi’s invention of the laws of perspective and Campin’s and Van Eyck’s development of the oil medium in the early hours of the 15th century—even as momentous for our twentieth century as were the shattered and re-combined forms of the Cubists and the pioneers who explored “simultaneity”, psychic symbolism and free association. (1)

Fig. 1

Returning to 1838, to Wheatstones stereoscopic drawings in the light of what was to boil out of Paris and London by Turner, Constable, Delacroix, Corot, Daguerre, Plateau, and to the oncoming tide of Courbet Manet, Monet, Seurat and Cezanne, one can be stirred by the lonely singular event portrayed in the stereoscopic drawing of two cubes by Wheatstone (Fig.1). If it meant little at the time to artists, too shocked by Daguerres “sun-pictures” and Talbot’s “The Pencil of Nature”, it now means the eclipse of our monoscopic view of the picture surface as a staging arena for plastic form and the beginning of a new space aesthetics of air, light, form, color—all discharged into the openness of windowless space.

Now awakened from its long sleep, the discovery by Wheatstone of the psycho-optical consequences of our binocular vision of reality, one sees that this is but the product of our two spaced-out eyes rendering two different retinal views of forms in the visual field. Two views, however, brought into a cyclopean fusion by the mind to render a profound single spatial awareness of reality—as reality is. Aware of this phenomenal rendering, Wheatstone wrote:

“It will now be obvious why it is impossible for the artist to give a faithful representation of any near solid object, that is, to produce a painting which shall not be distinguished in the mind from the object itself. When the painting and the object are seen with both eyes, in the case of the painting two similar pictures are projected on the retinae, in the case of the solid object the pictures are dissimilar; there is therefore an essential difference between the impressions on the organs of sensation in the two cases, and consequently between the perceptions formed in the mind; the painting therefore cannot be confounded with the solid object.” (2)Despite this remarkable achievement and prescience of Wheatstone, all of the progress and innovative developments of painters to his time (and yes, ours) to arrive at “a painting which shall not be distinguished in the mind from the object itself”—all were doomed to failure in spite of the incredible monoscopic illusionist successes of Van Eyck, Raphael, Heda, Zurbaran and Harnett.

It remained for Wheatstone to make the singular discovery that when we view a cube which is set before us and when we close one eye and then the other, it is apparent that we see two distinctly different appearances of the cube. While corroborations of this fact can be traced back through illustrious writings of Francis Agullonius, Baptista Porta, Leonardo Di Vinci, and even more into the remote past—to Galen and Euclid, it remained for Wheatstone to produce the first stereo- synthetic form and the means to achieve a conscious stereopsis of it in the mind. It must have been an extraordinary moment of insight when he realized that when two outline drawings representing the binocular view of a cube might become fused together, then this image would be accepted by the mind as a concrete solid existing in the same real spatial sense—as though one could reach out to touch it. Indeed this was the case. Wheatstone devised a simple mirrored apparatus to aid the cause of fusing his three-dimensional drawings. He called this device a Stereoscope (Fig.2). Wheatstone does not appear to discuss, at any length, the direct vision viewing of stereo pairs, nor does he suggest that he has delivered to the visual arts a new revolutionary method. He speaks to this, however, in these words:

“For the purposes of illustration I have employed only outline figures for had higher shading or coloring been introduced it might be supposed that the effect was wholly or in part due to these circumstances, whereas by leaving them out of consideration no room is left to doubt that the entire effect of relief is owing to the simultaneous perception of the two monocular projections, one on each retina.. But if it be required to obtain the most faithful resemblances of real objects, shadowing and coloring may properly be employed to heighten the effects. Careful attention would enable an artist to draw and paint the two component pictures, so as to present to the mind of the observer, in the resultant perception, perfect identity with the object represented. Flowers, crystals, busts, vases, instruments of various kinds, etc., might thus be represented so as not to be distinguished by sight from the real objects themselves” (2) (Fig. 3).

Were it not for the invention of the photograph these words might have fired the new spatial art. One might imagine where this revolutionary concept would have taken Manet, Monet, Seurat or Cezanne. Within six months of delivering his paper to the Royal Society, Wheatstone had already conceived of asking Fox Talbot and Henry Collen to provide him with photographic Talbotypes of statues, buildings and people. Since then photography has continued to utilize this astonishing discovery.

Fig. 3

We must return back to the moment before the photographic stereo view of reality overwhelmed Wheatstone and his contemporaries. A mere seven score years is but a moment in the strata of history—but the soil is now ready. Today we are dealing with the possibilities that entire orchestrations of color forms can be made to exist synthetically in a binocular space-field that is itself consonant with reality. The phenomenon of the Cyclopean Eye which miraculously renders our visions of the pristine, sylvan landscape now prepares us for the new stereoscopic art. Oliver Wendell Holmes, speaking in the year 1859, (Atlantic Monthly) might as well have directed these words to us when he wrote:“Nothing but the vision of a Laputan, who passed his days in extracting sunbeams out of cucumbers, could have reached such a height of delirium as to rave about the time when a man should paint his miniature by looking at a blank tablet, and a multitudinous wilderness of forest foliage or an endless Babel of roofs and spires stamp itself, in a moment, so faithfully and so minutely, that one may creep over the surface of the picture with his microscope and find every leaf perfect, or read the letters of distant signs….just as he would sweep the real view with a spyglass to explore all that it contains.” (3)

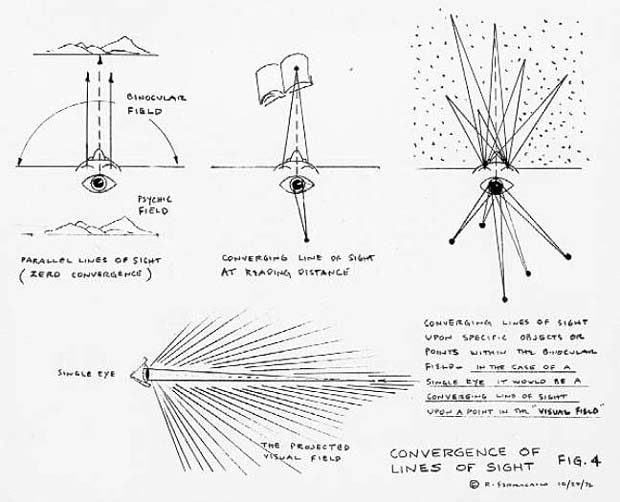

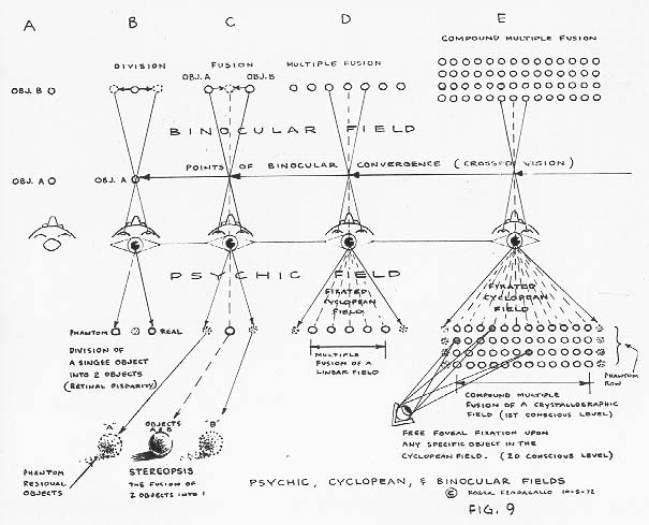

Though Holmes was referring here to the art of stereo-photography, this augury is but a stone's throw to an art of pigment, dye and ink. When the art of stereo-drawing and binocular disparity is mastered, one is within reach of a totally new aesthetics; an art of undetermined power—radically different, and basically new, whose only requirement will involve a capacity at everyone’s disposal who has normal binocular vision—the converging of lines of sight.This will require some examination of our binocular powers of vision. Two distinctly different projections of outside environments, falling upon the active retinal screens of both eyes cause the unexplainable, as yet hidden, power of consciousness to form a coherent, corespondent synthesis of the outside environment. When we fix our eyes, in a relaxed manner, upon the most distant reaches of a landscape, both eyes, are said to be staring with parallel lines of sight. (Fig. 4) Each eye, under these circumstances, is rendering its own different view of what might be a line of mountains. We may say that in the “mind’s eye” the images of the mountains have coalesced—fused into one image; as though we had an eye in the middle of our foreheads. In a sense, metaphorically, we have; we will refer to this as the cyclopean eye. (Hering, “oeil de cyclope imaginaire,” 1867)

Vision is mainly, however, concerned with convergence. Now as we look with both our eyes at specific objects located within the binocular field, from six inches to as far as we can see, we are rotating our eyes to converge two lines of sight upon an object. Our eyes can accommodate to focus and converge upon any form, anywhere in the visual field, with fixed attention, or with saccadic strokes. A single eye can do just as well, in the sense that the visual field is formed by the eye into a great cone of space—like a giant cyclone light flux 150 degrees wide. The eye of the cyclone, at its apex corresponds to the fovea of the retina which is the seat of our sharpest vision. One has a view of it by imagining a fine pencil of laser light emerging from the vanishing point of some self-directed linear perspective. All of the visual cues available to painters today to suggest distance and depth are entirely the domain of the single eye. But when both of these great visual cones converge upon an object in space—a profound property of vision emerges: stereopsis. Two retinal screens, not one, signal the cascading light show from outside the lens window of the eye to the cyclopean eye which opens to consciousness a psychic field consonant with the binocular field. (Fig. 4)

The more conscious we are of the spatial distinctions within the vastness of this fused, binocular-psychic space, the richer it can be said is our “stereopsis”. The key to our sensation of stereopsis is through two well known factors acting together: Convergence and Disparity. (4)

Fig. 4When both retinal cones converge upon a specific object in space, the eyes have found the range, so to speak, and the mind computes an accurate sense of distance. Binocular convergence involves the fact that our eyes are separated by a width of about 2 ½ inches. With this width serving as a base, our two lines of sight converge upon specific objects in space, spraying a profusion of triangular fixations upon them. With each fixation, a train of focal adjustments for each eye lens issues simultaneously as the eyes fix upon a distant aircraft, a nearby tree, or an ant passing over a leaf. The brain gives a critical evaluation of both factors and computes its sense of definition, distance and scale. Acting in concert with triangulation and focal accommodation is the brains computation of the shifted differences observed in objects that are seen separately by the left and right eye. This is called binocular or retinal disparity. (Parallax-displacement-shift) It is absolutely critical and important to our sensation of depth perception.

Fig. 5, No.1 to 5

By examining Fig. 5, No. 1 to 5, one can easily ascertain the fact that we see everything double except for the area around the foveal point of convergence of the primary lines of sight. Unconsciously, we simply pay little attention to this double vision unless we make a point to observe it as indicated by the diagrams. The mind however, compares and regards this rain of light bombarding the retina, with all its subtended angles and shifts of position, with computed finesse. Disparity as we shall see, will be at the center of the new space aesthetics.

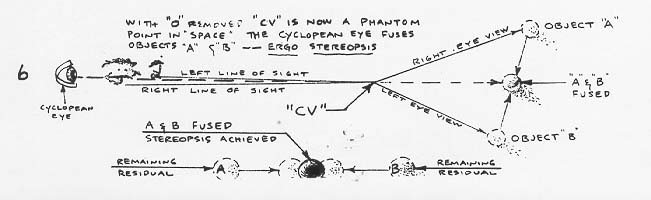

Connected with convergence and disparity, and important to this thesis, will be the realization that just as one has the ability to converge upon these words, any one can just as easily acquire the skill of crossing the visual axes in an imaginary space. (5) This essential factor, combined with disparity, opens the way to learning the methods and skills in both the construction of primary binocular forms and the viewing of them. The illustration in Fig. 5, No. 6 suggests that a left and right line of sight can be

brought to cross in space at an imaginary point (cv) to fuse two objects (A & B), at a distance, into one. This imaginary point is obtained by fixing the lines of sight at about reading distance, usually by staring ahead (obtaining a fix) through the index finger. Obtaining such a “fix” upon the tip of the index finger will cause any pair of objects in the distance, two balls for example lying along the same path of sight, to coalesce into one new ball at the center position. The two original balls remain in sight, as two residual-phantom images. This can all be very easily demonstrated another way by using only the fingers. Simply raise the forefinger and

Fig. 5, No. 6middle finger of one hand into the familiar V sign, at arms length. Bring the tip of the finger of the opposite hand between the eyes at about reading distance and stare ahead. By closing one eye and then the other, one can corroborate precisely what is illustrated in Fig. 5, No. 6.

As a further consequence of this discussion of disparity and convergence it will help to look at Fig. 6 which illustrates the two distinctly different methods of viewing binocular constructions. The method of parallel lines of sight (staring fixedly ahead beyond the pairs) and the method of crossing lines of sight are contrasted. Viewing stereo constructions by means of parallel sight limits picture size (2 ½” separation between image objects) which is a physical limitation based upon the interocular separation of the eyes. This special kind of vision, then, limits itself to small scale pictures and figures.

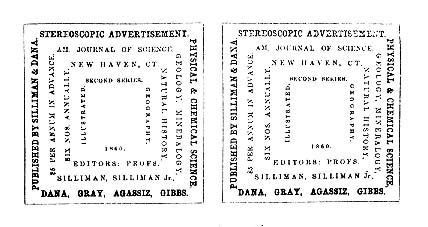

An interesting example of the early use of this idea, published in 1860, is the advertisement shown in Fig. 8. This example serves to demonstrate the arrangement of words as merely decorative as distinguished from the expressive-spatial interrelationship found in 3-D Concrete Poetry. (6)

Fig. 8

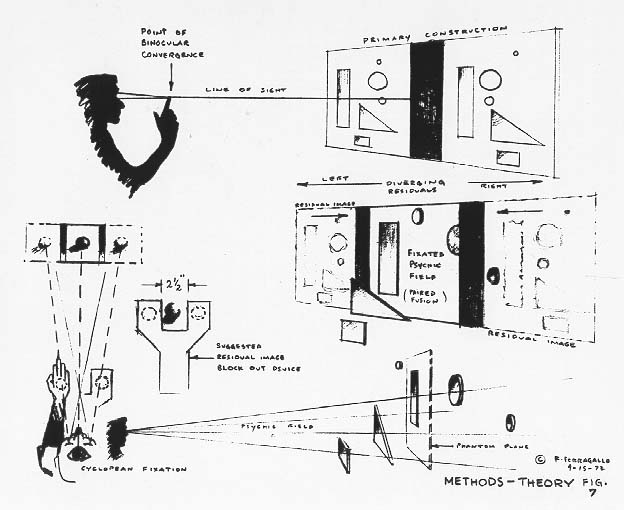

It is the crossing of lines of sight that must draw our full attention. This is of great importance because there is no limit to the size of images and constructions; nor is there a limit to the distance from which they may be viewed. Crossing lines of sight is central to the proposal in this thesis. It must be noted that both of these methods (parallel and cross vision) of viewing stereo constructions have quite different properties. This difference will be apparent as you try to view the constructions in Fig. 6. You will note an inversion of the spatial figures if you use one and then the other method of viewing the small figures. The large stereo drawing at the top of the page is impossible to view with parallel sight because the homologous points are beyond 2 ½ inches. With crossed vision they present no problem. Accomodating yourself to crossing your lines of sight brings the viewer to within reach of the new space art—an art whose only requirement will involve the necessity of staring fixedly at the center point between the dyptich images of a stereographic construction. (Fig. 7) There will be the essence of hypnosis in the stare, for it will project one into space to interlock with the painted color forms until he is no longer outside but virtually inside—in aesthetic empathy with whatever visual forces have been unleashed into the openness of space. The act of seeing this new space is simple: You, the viewer, may use a finger as a reference to crossing your lines of sight, or you may block out the left and right images with your hands; or use the suggested cardboard block-out card shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7You stare—you willfully converge your eyes at your finger tip and at the same time observe the dual construction ahead as it divides into three images. It is at this instant that you stare at the third central image—you gaze—concentrate—meditate fixedly upon the center image until it comes on you—and it will—with the clarity and power of sudden revelation. The painted forms will be seen to exist in real space, actually and concretely, as if in the nether world of dreams you have just opened a middle eye—a cyclopean power. Oliver Wendell Holmes, writing in Atlantic Monthly, July, 1861, in an article titled: “Sun-Painting and Sun Sculpture” speaks of this faculty:

“Perhaps there is also some half-magnetic effect in the fixing of the eyes on the twin pictures, --something like Mr. Braid’s hypnotism……At least the shutting out of surrounding objects, and the concentration of the whole attention, which is a consequence of this, produce a dream-like exaltation of the faculties, a kind of clairvoyance in which we seem to leave the body behind us and sail away into one strange scene after another like disembodies spirits.”(7)

When you will have once raised the lid of the middle eye—the cyclopean power will remain open and becomes easier—finally effortless. You will have before you a visual field of immense spatial depth, an arena where the total of the visual vocabulary will be given the distinction of reality and life in space. A powerful intensification of communication—of communion with form. Elements which formerly were locked within the monocular field are now free to exist above, within, and beyond the surface upon which the forms themselves are painted. There are no longer any barriers to position or place in stereo space—no boundaries. Any diptych pair can be paired with any other to render a sense of boundless repetition in all directions. (Fig. 9 and Fig.10) With the simple act of cyclopean fusion even the very walls of architecture will dissolve away into immense stereo spatial fields of crystalographic color patterns. The physical carrier of form, be it canvas, paper, concrete, fresco will no longer have any meaning. Dot, Line, Plane, Volume, Space, Color and Texture will orchestrate in open space where formerly the dynamics of such spatial entities were displayed in concert with the surface. In the new aesthetics of stereo-space the surface dematerializes and evaporates itself into space. It is quite remarkable that this dematerialization of the picture surface was described in some detail by Sir David Brewster in his book “On the Stereoscope” published in 1856. In a Chapter titled: “On the Union of Similar Pictures in Binocular Vision”, he describes experiments on large surfaces that he covered with similar plane figures. Brewster stated:

“If we, therefore, look at a papered wall without pictures, or doors, or windows, or even at a considerable portion of a wall, at the distance of three feet and unite two of the figures, two flowers, for example—at the distance of twelve inches from each other horizontally, the whole wall or visible portion of it will appear covered with flowers as before but as each flower is now composed of two flowers united at the point of convergence of the optic axes, the whole papered wall with all its flowers will be seen suspended in the air at the distance of six inches from the observer! At first the observer does not decide upon the distance of the suspended wall from himself. It generally advances slowly to its new position, and when it has taken its place it has a very singular character. The surface of it seems slightly curved. It has a silvery transparent aspect. It is more beautiful than the real paper, which is no longer seen, and it moves with the slightest motion of the head. If the observer, who is now three feet from the wall, retires from it, the suspended wall of flowers will follow him, moving farther and farther from the real wall, and also, but very slightly farther and farther from the observer. When he stands still, he may stretch out his hand and place it on the other side of the suspended wall, and even hold a candle on the other side of it to satisfy himself that the ghost of the wall stands between the candle and himself.”

It seems impossible that these words should lie buried for 116 years. And it is even more astounding that this marvelous description by Brewster could possibly have been and still can be an art involving repeated patterns, continuous friezes, whole architectural assemblages of crystalographic color-forms suspended in air, existing beyond and beneath a dematerialized planar surface. Buried in the 19 Century, and clearly within the scope of this statement—of the new aesthetics, also lie experiments by Brewster, H. W. Dove, and O. N. Rood on what they called the theory of “Lustre”. This involves the binocular fusion of color fields giving riseto phenomenological kinds of atmospheric, optical color mixture. The monocular color fields of Seurat and color field abstractionists today will pale before the new possibilities of binocular color fusion. Returning to Brewster, one cannot underestimate the enormous possibilities suggested by him. Not only is he saying that the surface has dematerialized, but that stereoscopically paired graphic forms can be multiplied n-times-in all directions. In Fig. 10, one of Wheatstone’s paired drawings has been organized as a potentially n-crystalographic field—either by the method of parallel sight or by cross-viewing, you will immediately witness something very astonishing: One will find that his “Cyclopean” sense, the unconscious, (Gestalt) or whatever it will eventually be understood to be, will hold the entire field fixated while at the same time, he (the viewer) is free to direct his eyes to any portion of the field—to focally converge upon any particular isolated point, figure or cluster of figures. How does the mind hold so large a psychic field of visible forms constant while permitting a foveal examination of details in any direction? It is as though one has induced hypnosis to one level of mind while permitting another level of mind virtual license.

One will find, too, that the more he exercises this psycho-optic ability, the easier and easier it becomes to fixate both the field and its detail. After a time, it will seem quite natural to cross-view synthetic forms as it is natural to converge the eyes normally upon objects. This suggest the vista of an aesthetics that will undoubtedly bring forth a very powerful (psychosynthesis) transcendental, meditative art. This binocular art may also have within it the power to bridge the gulf between the traditional Western and Eastern conceptions of space. Here, then, will be an aesthetics that will involve the philosophical, historical, spatial invention of both East and West into an unparalleled new synthesis. The picture surface has only been understood, up to now, monoscopically, as though we were all inhabitants of some “Flatland” (9). This is not to say that the great tradition of monoscopic painting is to be occluded any more than it is to view the techno-spatial inventions of the last 35,000 years are suddenly brushed aside. Monoscopic, flat field, or space-illusionist art whether it be Paleolithic, Medieval, or of the nature of “The Garden of Delights”, Michelangelo’s “Sistine Ceiling”, “La Grand Jatte”, “Guernica”; all of these are among the treasured heritage of the past. The long history of hard-won innovations of rendering visual illusions upon planar surfaces is an immense fund of techno-visual language. From the Aurignacian to the present, the list of spatial invention is long: vertical position, overlapping planes, diminution of size, aerial and linear perspective, inverted and multiple perspective, foreshortening, shadows, texture gradients, optical illusions, interpenetrating form and space, advancing and receding color fields, two dimensional space division, illusions of motion and after images. A stereo art cannot properly exist without the involvement of these important monoscopic space illusions. What is called for now is the re-integration of this knowledge with our psycho-binocular powers of stereopsis—a sensing of the three-dimensional space field that lies both within and without us. This is both possible now and necessary. Speaking both to the art of pigment, dye and ink and to the art of light sensitive emulsions—inevitably they must now be driven together. Stereoscopic aesthetics will be an arena that will see the plastic forms of the past 100 years fusing into staggering arrays of re-combinations of familiar and unfamiliar forms, new synthesis, shimmering-lustrous color fields; all existing in air—a space without a canvas base, paper base or physical carrier whatever. There will be complete and remarkable deceptions of the physical and mental eye. The space outside our heads will match the space inside our minds. It will mean the discovery of a mental force that will warp two constructions into one—into single a cyclopean phantom, as though our primitive, infantile diplopia were being brought into fusion and synthesis. We are at the beginning of a new era in the visual arts no less momentous than was our thrust into the depths of space, which was to link the surface of the earth with the Lunar Sea of Tranquility. We looked back upon ourselves from that luminous Astral sea with psychic shock and a compelling awareness of where we really are. No less are we enthralled by the vastness of inner-space. We can truly be aware that this intensification between ourselves, this planet “space-ship earth” coupled with our relentless bombardment of atomic nuclei will all inevitably drive the arts (as we know them) into totally new perspectives. The time is now. The tools are here: they exist in the photographic arena of Holography, Xography, Vectographs, Anaglyphs, polarized stereo pairs, wide screen stereo-panoramas, stereo-cinematography and stereo-video. They are before those of us who must now awaken the sleeping cyclops to reform – and to refashion in paints, dyes and inks, synthetic assemblage orchestrations of color-forms in a psychic-binocular space.© Roger Ferragallo 1972 REFERENCES

1. Wheatstone, Charles. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London,“On Some Remarkable and Hitherto Unobserved Phenomena of Binocular Vision,”June 21, 18382. Ibid., page 3763. Holmes, Oliver Wendell. “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph”, Atlantic Monthly,June, 1859, pages 738-7394. Julesz, Bela “Foundations of Cyclopean Perception”, Univ. Chicago Press, 19715. Krause, E.E., Reading in 3-D, Research and Development, Nov. 1972, pages 38-406. Layer, H.A., Space Language: Three Dimensional Concrete Poetry, Media and Methods,January 19727. Holmes, Oliver Wendell, “Sun Painting and Sun Sculpture,” Atlantic Monthly, July 1861 pages 14-158. Brewster, D., The Stereoscope; It’s History, Theory and Construction with its Application to the Fine and Useful Arts and to Education, London: John Murray, 1856, Chapter VI, page 919 Layer, H.A., Exploring Stereo Images: A changing awareness of space in the fine arts, Leonardo 4 233, 1971

ILLUSTRATIONS

Fig. 1 Stereoscope-Wheatstone, 1838Fig. 3 Wheatstone – Original page of Stereo Constructions, 1838Fig. 4 Convergence of Lines of SightFig. 5 Analysis of the Binocular Disparity Field and StereopsisFig. 6 Parallel Lines of Sight -- Crossed Lines of SightFig. 7 Methods – TheoryFig. 8 Stereoscopic Advertisement, 1860Fig.10 N-Crystalographic Field of Wheatstone’s Line Figures